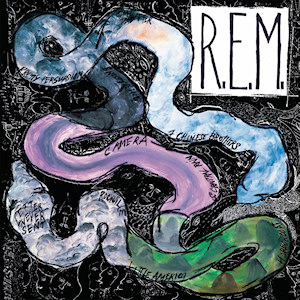

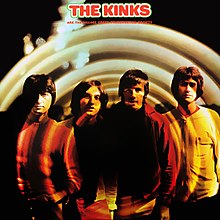

The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, The Kinks, 1968

Introduction

In 1967, The Beatles released a double A-side, “Strawberry Fields Forever” on one side and “Penny Lane” on the other. Not bad. They are both beautiful and groundbreaking songs, musically and lyrically. “Strawberry Fields” is brimming with mysterious mellotron sounds and psychedelic tape loops, and “Penny Lane” makes a piano and a cornet and a bass guitar sound like distilled sunshine.

Most importantly to rock music history, however, both songs are about nostalgia. Allegedly.

Ian MacDonald, who wrote a really great and comprehensive book on The Beatles called “Revolution in the Head,” saw the double A-side as setting the standard for the “English pop-pastoral mood” that bands like Pink Floyd, Traffic, and Fairport Convention came to typify. He also viewed the songs, particularly “Strawberry Fields,” as ushering in English psychedelic music’s preoccupation with “nostalgia for the innocent vision of a child.” Another author, David Howard, agrees, saying “Strawberry Fields” was a direct parent of Pink Floyd, The Move, The Smoke, bands that all released debut albums right on the heels of the Beatles’ double-A.

I don’t disagree with these scholars. It would be a dumb exercise to argue “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane” didn’t set off a sea change in the rock music industry for a variety of reasons. I actually do disagree, though, that both of those songs were so influential because they were about nostalgia. I think that double-A is nostalgic, but I don’t think it is about nostalgia. The band actually writing about nostalgia in the 1960s was The Kinks, and they succeeded in doing so by having a complex relationship with the past, rather than simply evoking it.

What’s There to Preserve?

It’s right there in the album title. “Preservation.” The Kinks’ 1968 album, The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, is supposedly about preserving something. Preserving what? The album opener, which lends its name to the album’s title, suggests The Kinks want to preserve various ancient British institutions such as strawberry jam and vaudeville, as well as tons of others that I can’t pretend to understand, like Desperate Dan, Old Mother Riley, and the George Cross. Look them up if you’re curious, or think of them fondly if you’re an elderly Brit. The chorus espouses that The Kinks are “preserving the old ways from being abused/protecting the new ways for me and for you/what more can you do?”

It’s a nice idea, and the lyrics fall in line with the “Penny Lane” line of thinking. The barber shaves another customer, the fireman rushes in, etc. Ray Davies wastes no time subverting the album’s supposed central theme, though. Track 2 is “Do You Remember Walter,” an incredible song about an old friend. Sounds like a ripe opportunity for some more nostalgic pining. The narrator of the song tries his hardest to engage in it, too. In the first verse, he innocently asks Walter whether he remembers “playing cricket in the thunder and the rain” and “smoking cigarettes behind the garden gate.” In the second verse, he more seriously asks Walter if he remembers their hopes and dreams, but acknowledges they were “not to be.” He asks Walter, “I knew you then, but do I know you now?” In the last verse, he gravely acknowledges the reality of the present. “Walter/if you saw me now you wouldn’t even know my name/I bet you’re fat and married and you’re always home in bed by half-past eight/and if I talked about the old times, you’d get bored and you’d have nothing more to say.” There’s your song about nostalgia. Things change, regardless of any aforementioned preservation efforts. Walter’s different now, but Davies decides to ignore it, ending the song by saying “people often change/but memories of people can remain.”

Those two songs in tandem tell you all you need to know about the themes on The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, but almost every song on the album is about nostalgia somehow, and the ones that are seemingly “pure” nostalgia are all informed by the ones that take a darker approach to memory.

I Want to Be Back Where?

Two more songs on the album play back to back and present really interesting, conflicting ideas when thought of together. The first is “Animal Farm” (not that one). The narrator of “Animal Farm” hates city life, and wants to escape it. “This world is big and wild and half insane,” he says. He wants to leave the city and live “among the cats and dogs and the pigs and the goats.” Did Ray Davies actually even grow up on a farm? Tough to say–I didn’t do much research. I kind of doubt it, though. Anyway, he explains to the girl in the song that “it’s a hard, hard world/if it gets you down/dreams often fade and die in a bad, bad world,” but he’ll solve those problems by taking her “where real animals are playing/and people are real people, not just playing.” It’s another nice sentiment worthy of the nostalgic title. At least until it is immediately followed by “Village Green,” a devastating song about nostalgia so evocative it makes the song before it about nostalgia, too.

“Village Green” actually begins pretty similarly to “Animal Farm.” The narrator outlines a village green that is “out in the country/far from all the soot and noise of the city.” He hasn’t been in a while, but he remembers the church with the steeple, the girl called Daisy, the fresh air, Sunday school. It would, theoretically, be a good place for the “Animal Farm” narrator to go to be with real animals and real people. Much like the narrator in “Walter,” though, Davies finds himself disappointed with the reality of that village green he remembers so fondly. “Now all the houses are rare antiquities/American tourists flock to see the village green.” Daisy’s still there, but she’s “married Tom the grocer boy/and now he owns a grocery.” The town moved on without him. Still, he avows to return. He’ll “see Daisy/and we’ll sip tea, laugh, and talk about the village green.” Fat chance.

Wicked Annabella

Even the few songs on the album that are not about nostalgia are implicitly about nostalgia in some way. “Wicked Annabella” is a fantastic psychedelic tune about a strange witch who haunts children. Your basic ’60s song topic. Hidden in the weird, nightmarish lyrics, though, is another lesson on the realities of nostalgia. The song warns children not to go into the woods at night, because “underneath the sticks and stones/are lots of little demons/enslaved by Annabella.” In other words, nostalgia, a perfectly normal aspect of life, could be ugly or unwanted if you look at it too closely. Annabella is the manifestation of that unwanted result.

Don’t Show Me No More, Please

And finally there’s the two songs about photographs. The clearest one-two punch on the whole album. First, there’s the innocuous “Picture Book.” A nice, cheery tune about old family pictures, pictures taken “a long time ago/of people with each other /to prove they love each other.” There’s pictures of fat old Uncle Charlie and breakfast in sunny Southend and the whole thing ends with “na na na’s” and “scooby-dooby-doo’s.” Looking at those old photos makes the narrator feel good! Well, maybe not.

The closing track on the album is “People Take Pictures of Each Other,” which is also about people looking at old family pictures, but nothing about the song makes me feel good. Like in “Picture Book,” people take pictures to show they love one another, but the lyrics actually read “just to show that they love one another.” It’s more cynical. Additionally, people take pictures of the summer “just in case someone thought they had missed it” and to “prove that it really existed.” The narrator scoffs at the idea. “You can’t picture love that you took from me/when we were young and the world was free/pictures of things as they used to be/don’t show me no more, please.” In the most British way possible, Davies really sounds angry here. The whole album examines nostalgia, and Davies ends up summing it all up with “don’t show me no more, please.” He’s done with the whole idea. It’s pointless. I can’t fully buy that, though, because in the same way that the negative subverts the positive on this album, the inverse is also true. For every “Village Green,” there’s an “Animal Farm.” And for every “Do You Remember Walter,” there’s a “We Are the Village Green Preservation Society.” I don’t think Davies is angry–I think he’s mournfully resigned. He wants things exactly the way he remembers them, but he knows they’re not. He wants nothing to change, but he knows they will. So, he wraps up the album. “How I love things as they used to be/don’t show me no more, please.”

Wrapping Up

I’m realizing now I made the album sound like a bunch of poems. All those words, they’re actually all set to music. And the music is fantastic. It’s The Kinks, for God’s sake. There are great chord progressions, there are interesting piano compositions, there are amazing harmonies, there are inventive drum fills. It’s all there. I just forgot to talk about it. Because the music, while incredible, is not the standout part of this album. What make The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society an all-timer is that the album, the whole thing, is about something. And not about something in the way that a “concept album” like The Wall is about something. It’s about something in the way that a television show or a movie is about something. It takes an idea, looks at it from several different angles, sets it to music, and lets us figure out what it all means.

“Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” and Pink Floyd and The Move and The Smoke and whatever, they were all of their time, or maybe ahead of their time. I think Ray Davies was completely out of time when he wrote this album. Which is why I think it resonates so well 55 years later. Maybe it’s because The Kinks had no interest in the psychedelic scene. The band’s bassist, Pete Quaife, said he “just let the whole flower people, LSD, love thing flow over my head.”

As for Davies, he had this to say in 1968, a year of immense social upheaval:

“Everybody’s trying to change the world; I’ve tried and I’ll probably try again, but I don’t think you can change Britain that much, because we’re the way we are. So I’m just going to try and hang on to a lot of the nice things.”

Don’t show me no more, please.